The complexity and speed of change create uncertainty. Uncertainty leads to wrong decisions. At the same time, not making a decision is also making a decision. Risk management helps to counter this uncertainty.

There is the unfortunate cliché that risk management is boring and risk managers are pessimists and panic-mongers. But this need not be the case. Agile risk management helps to overcome this common view.

What needs to change?

Agile methods require daily collaboration and appropriate and regular communication between all those involved. Questioning assessments and evaluations and, if necessary, adjusting to new situations or information are essential. Unexpected events and constant changes in external circumstances are part of daily business and should not jeopardize achieving business goals.

Being agile means adapting quickly to new situations and master challenges or exploit opportunities. Agile values, principles, and methods help to achieve this.

… we are supposed to be taking risks. So, we don’t think of risk management as trying to minimize risk. That’s actually the way to prevent creativity. Rather, is to do risky things and then when they go in some unpredictable path, to be able to respond to it.

When companies focus on minimizing risks, they simultaneously reduce opportunities. To seize opportunities, we need creativity and courage. Courage requires confidence. Even though Ed Catmull’s quote is from a 2008 podcast, it is still relevant today. Risk management must change so entrepreneurs and employees can leave their comfort zones and try new things. This is the only way to exploit opportunities effectively.

Everyone is required

Everyone is required to obtain the best possible information. Everyone provides the expertise for their work area to identify and evaluate risks and opportunities and make better decisions. Communication is a critical factor in this process. Before we can effectively share our knowledge with others, we need a common understanding and language that makes misunderstandings avoidable.

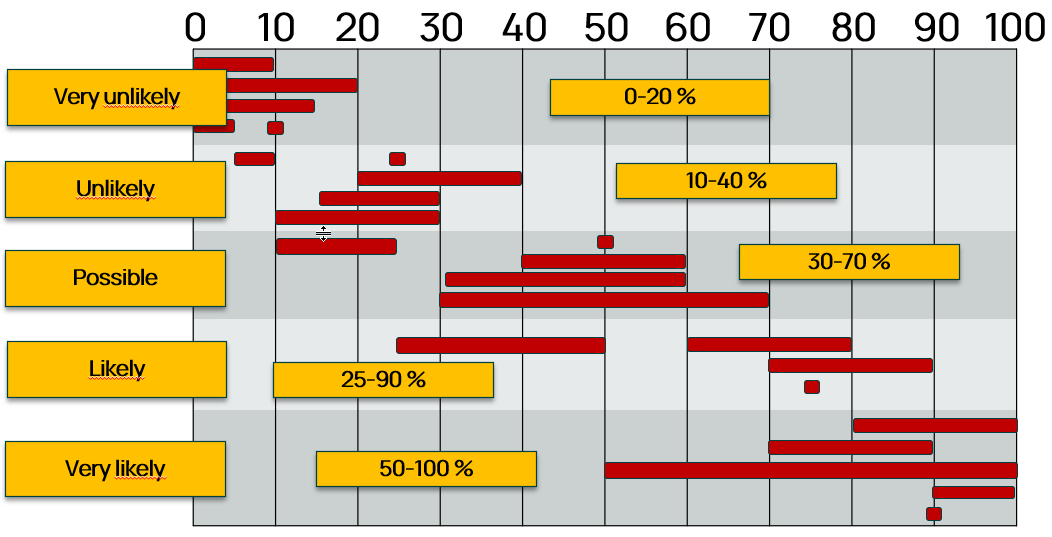

Probability terms such as “low, medium, or high” are standard in risk assessments. When describing impact, terms range from “negligible to catastrophic.” But what does it mean? Everyone understands something different by it. Thus, misunderstandings are bound to occur, leading to wrong decisions.

The figure shows a typical distribution of responses from workshop participants to the question of how they define the probability in percent for the terms mentioned on the left.

The results suggest that more than the implicit differences in personal definitions are necessary to compare assessments. To avoid this, use numbers and comparable scales.

Probabilities and opinions

Probabilities are expressed in percentages from 0% (impossible) to 100% (certain). Most people have learned that the percentage value indicates the relative frequency of occurrence of an event. For example, the probability of rolling a 6 is one in six or 16.6%. Of course, we don’t know this for arbitrary events because we need more information. Here is where Bays’ concept of probability comes in. The percentage value is a measure of our belief. We express our confidence in a number comparable to other assessments.

While dealing with probabilities is often a challenge for us, there is one value that we are very familiar with the monetary value!

What does it cost?

What is the cost or profit if a particular event occurs? Since it is not easy to give a concrete sum, we define an interval in which the actual value is likely to lie. Using money as a scale makes estimates of impact comparable. Communication of beliefs and estimates is more explicit in this way.

Is there an advantage to expressing beliefs and estimates in numbers and comparing them? The answer is yes because, in this way, experience and intuition become visible and valuable for decision-making.

The value of intuition

Our brain can recognize patterns in complex contexts. This ability is also known as intuition or gut feeling. It enables us to make quick and unerring decisions where rational thought and analysis take too long. However, there are also limits. In terms of evolutionary history, humans have lived most of the time in a stable situation over a long period. Our ancestors had enough time to learn to use their intuition in such a way that it delivered results in precisely that situation.

If external circumstances change, our gut instinct delivers results correctly in the previous situation but may be catastrophically wrong in the changed situation.

We trust our gut instincts so that we don’t hesitate to apply potentially vital decisions. Questioning or analyzing could mean the difference between life and death for our ancestors in the wilderness. Today, athletes use this skill in team sports like soccer or basketball, where quick reactions are required. Practicing moves and analyzing past games helps to make the right decision intuitively and without long thinking.

Using intuition and experience in decision-making in projects or the company is familiar. However, the situation has changed. The reasons are exponentially advancing interconnectedness, digitization, and an increasingly unstable political situation. As a result, markets are changing much faster. Compared to sports, it is as if new rules apply to every game, but the players are not informed about them.

This new situation is the same for all market participants, so companies have many new opportunities to position themselves and effectively use the constant change.

Binary thinking

The question is: What is the benefit of intuition for projects and business decisions in a complex, fast-changing world? — Fortunately, the time for decisions is longer than in sports or the wilderness. Fast means faster than others. Since many companies still have very long decision-making processes, even a tiny improvement can provide a significant advantage.

If you don’t look at intuition in isolation but compare the results with other experts, it’s like different pieces of the puzzle coming together to form a more complete picture.

Of course, it is not helpful to insist on your point of view. Changing one’s mind is easier when binary thinking, i.e., right and wrong or yes and no, is replaced by any number of gradations in between. In this way, one’s assessment is not immediately incorrect, but perhaps only a few nuances less correct.

Risk aversion

But how is it that different experts evaluate the same facts differently? One possibility is mental bias.

For example, everyone has an individual attitude toward risk. Some people find it easy to take risks, while others shy away from them. The result is correspondingly different assessments. These personal mental biases are balanced by comparing and combining them with the results of others.

Other possible reasons are different experiences, levels of information, and perspectives.

Information and consistency

The ratings show considerable differences depending on how informed a person is and how the respective information is weighted. For example, a piece of information is rated too highly because someone has read a suitable news item on the Internet on the same day. This phenomenon is called availability bias.

Experts whose assessments and evaluations play a role in decision-making can learn how to improve their performance by analyzing and, if necessary, adjusting their thought processes.

Consistency with available information also plays an important role. For example, we quickly get distracted by case-specific information and ignore available, relevant statistical information, such as commonly known probabilities for events or sample sizes. This tendency is called the base rate fallacy.

The better the available information is used, and the more experts are willing to challenge and correct their estimates based on new information, the better the results. These results form the basis for decisions; a solid foundation makes good decisions.

But how do we know how good our estimates are and thus the basis for decisions?

Feedback

In agile product development, we often ask users for feedback. Based on the feedback, we review decisions and correct them if necessary. In this way, we learn more about the complex environment in which we want to present a successful solution.

When estimating the probabilities of random events, this possibility does not exist. Nevertheless, it is necessary to receive some feedback so that continuous improvement of results through learning is possible.

The Brier Score, proposed by Glenn W. Brier in 1950, can help. The basis for calculating the Brier Score is the predicted probabilities for the occurrence of events in a certain period, e.g., in the next year. At the end of the period, we know whether an outcome has occurred (1) or not (0). The Brier Score is updated to provide a value between 0 and 1. The best value is 0, and the worst is 1.

Using the Brier score, the quality of the estimated probabilities can be objectively checked and compared with previous results.

The estimate of the impact of events that have occurred is compared with actual costs or revenues. In future assessments, we can apply this knowledge to achieve better results.

What a coincidence

Complexity also means it is insufficient to independently consider probabilities for events and effects. It isn’t easy to intuit combinations of random events. Statistical methods can help but require special knowledge.

An alternative is to use quantitative models, such as those created with Excel or Jupyter Notebook. A simulation with randomly generated values for the occurrence and impact of events determines the probability of losses or gains based on the combination of all events and random values. This method is called Monte Carlo simulation. The results can be presented as a loss-exceedance curve and form the basis for further decisions.

Such models help to understand the phenomenon of chance better.

Limitations of models

Models enable the analytical consideration of many intertwined risks and opportunities. However, each model has its limitations. For example, some risks are unacceptable because they conflict with ethical and moral principles. In these cases, it is helpful to use ethical and moral behavioral guidelines as a basis for informed decision-making.

Conclusion

Risks and opportunities are two sides of the same coin. A rapidly changing world and increasingly complex markets offer new opportunities for companies. It is necessary to take risks to take advantage of these opportunities. Companies that adapt quickly to new situations have a decisive advantage. Good decisions are essential for this.

Agile risk management provides a framework for a modern, inclusive approach to probabilities, information, unconscious knowledge, and experience to improve assessments, evaluations, and decisions continuously.

Agile risk management puts people at the center of entrepreneurial action. The process is individually designed and constantly adapted to new circumstances.

Those who cannot find an answer to the question of the benefit of the current risk management system in the company should take action now. Those who still think risk management is unnecessary can only be wished good luck.